卑弥呼に関する覚書

Notes on Himiko

Bottle No.1 「欠史八代」と日本のはじまり

1. 卑弥呼の時代を考えるために──「欠史八代」とは何か

日本古代史を語るうえで、まず「欠史八代」という概念と、日本という国の起源について触れておく必要があります。

というのも、卑弥呼の時代をどう理解するかは、これらの問題と深く関わっているからです。

以下は、初代神武天皇から9代開化天皇までを並べてみたものですが、2代から9代までが天皇の事績が欠けている、つまり記述がないため「欠史8代」と言われるわけです。そして記述がない=架空とされており、初代神武も含め、9代までが架空の天皇で、10代の崇神天皇からが実在とされる見方が強いわけです。架空とされる9代の天皇と没年齢

代 天皇名

古事記による没年齢

日本書紀による没年齢

1

神武(じんむ)天皇

127歳

137歳

2

綏靖(すいぜい)天皇

45歳

84歳

3

安寧(あんねい)天皇

49歳

57歳

4

懿徳(いとく)天皇

45歳

77歳

5

孝昭(こうしょう)天皇

93歳

114歳

6

孝安(こうあん)天皇

123歳

137歳

7

孝霊(こうれい)天皇

106歳

128歳

8

孝元(こうげん)天皇

57歳

116歳

9

開化(かいか)天皇

63歳

115歳

2. なぜ「紀元前660年」が日本の始まりなのか?

日本の始まりは、紀元前660年という考え方があります。では、どうして日本の始まりが決められたのでしょうか?

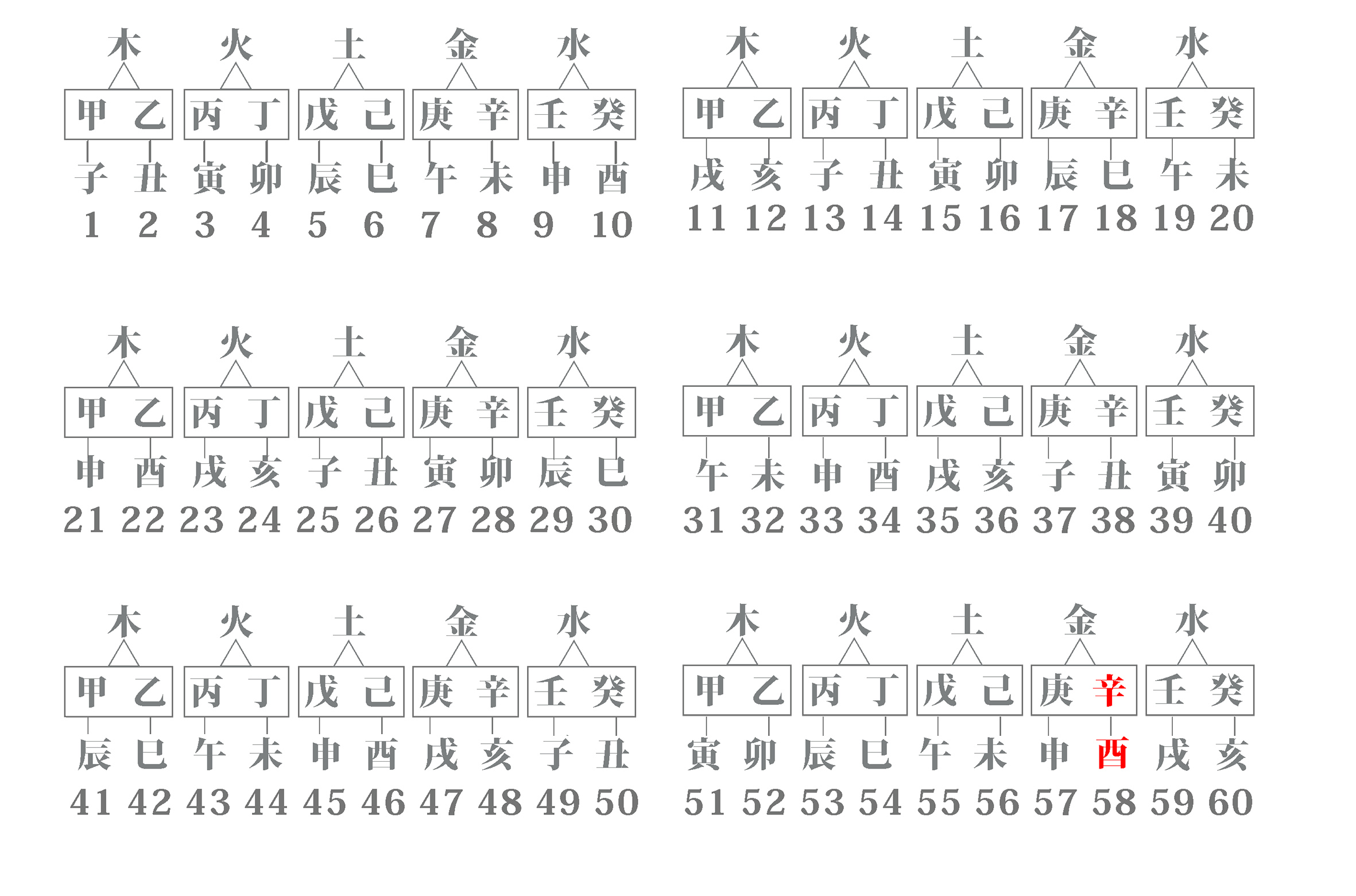

推古天皇の時代に中国から「暦」が伝わりました。それは、「甲・乙・丙・丁・戊・己・庚・辛・壬・癸」という十干(じっかん)と、「子・丑・寅・卯・辰・巳・午・未・申・酉・戌・亥」の十二支の組み合わせ、それをさらに「木・火・土・金・水」という五行を配当することで60年で暦が一回りするという60進法の考え方です。

これを表にしたのが上の図になります。「干支カレンダー」のようなものですが、この図の中に赤字で記した辛酉(しんゆう)の年があります。日本的な読み方をすると「かのと・とりの年」となります。60年に一度、「辛酉の年」が巡ってきますが、この「辛酉の年」は変革の年と言われ、これが21回繰り返された辛酉の年、すなわち1260年に一度の辛酉の年は大変革が起こる年とされ、暦が伝わった推古天皇の時代からさかのぼること1260年、つまり紀元前660年こそが日本のはじまった年に違いないとなった訳です。

ここに分かっている天皇を割り振っていったのです。事績のわからない、生没年不詳の天皇については、100歳以上生きたという風に、不必要に長生きさせないと帳尻が合わなくなってきました。

これは言い換えれば、これら天皇(当時は天皇という呼称はなく大王になりますが)は存在が確実視されており無視できなかったためではないでしょうか? 架空に作り上げるなら、もっと人数を増やし帳尻を合わせばいいように思うのです。これら存在したという天皇を増やしも減らしもできなかったのは、彼らが実在し、無視することができなかったからではないでしょうか?

では、これら9代の天皇(大王)が存在したとして、これらの天皇の実年代を割り出すことはできないのでしょうか?

3. 卑弥呼の時代と文献史料──神話から歴史へ

当時は日本には記録というものが存在しません。卑弥呼に関しては、中国の「魏志倭人伝」というものが唯一の文献史料と言われています。

ではこの「魏」という国ですが、これは三国志の、魏・蜀・呉の「魏」の国のことであり、これ以前は、中国では「後漢」の時代になります。そこで登場するのが、「後漢書」。これが後漢の正史になるのですが、その中に「東夷伝」というものがあります。普通は「後漢書東夷伝」と言われ、この史書に「奴国」であるとか「倭国」が、中国に使節を送ってきたという記録があります。

西暦57年には奴国が朝貢し「漢委奴国王」の金印を授かりました。これは日本史の教科書に出ているあまりにも有名な史実です。

次いで西暦107年には、倭の王が160人の奴隷を献上したことが記されています。

そして2世紀後半には倭国大乱と呼ばれる内乱が起きたことが記されていますが、これは「魏志倭人伝」にも「卑弥呼の登場」とともに記録されています。こう見てくると、どうも西暦1世紀には権力の集中した大王の存在が感じられます。推測ではありますが、この頃に日本の起源、つまりは神武天皇の時代を想定しても問題ないのではと思うのです。

そして2世紀後半の倭国大乱が記録され、卑弥呼の舞台設定が整えられました。

大和朝廷という呼称は適当ではないかもしれませんが、今、便宜上使うなら、大和朝廷の歴史の中に「卑弥呼」を位置付けることが可能となってきたわけです。◆ 次回予告:卑弥呼の出生をめぐって

今回は「日本のはじまり」と卑弥呼登場の背景までを扱いました。

次回は、卑弥呼の出生や出自について考察していきます。

Bottle No.1

— On the "Eight Undocumented Emperors"

and the Origins of Japan

1. Considering Himiko's Era — What Are the "Eight Undocumented Emperors"?

To understand the era of Himiko, we must first reflect on the concept of the "Eight Undocumented Emperors" in ancient Japanese history, as well as Japan's own origins. These topics are inseparably linked to the historical setting in which Himiko appeared.Below is a list of emperors from the first, Emperor Jimmu, to the ninth, Emperor Kaika. The reigns of the second through ninth emperors lack any verifiable historical records and are therefore collectively referred to as the "Eight Undocumented Emperors" (欠史八代, Kesshi Hachidai). Due to this absence of records, these early emperors—including even the first, Jimmu—are often considered mythical figures. In contrast, many scholars regard the tenth emperor, Sujin, as the first historically plausible sovereign.

The Nine "Mythical" Emperors and Their Recorded Lifespans

No.

Emperor

Lifespan in the Kojiki

Lifespan in the Nihon Shoki

1

Emperor Jimmu

127 years

137 years

2

Emperor Suizei

45 years

84years

3

Emperor Annei

49years

57years

4

Emperor Itoku

45years

77years

5

Emperor Kōshō

93years

114years

6

Emperor Kōan

123years

137years

7

Emperor Kōrei

106 years

128 years

8

Emperor Kōgen

57 years

116 years

9

Emperor Kaik

63 years

115 years

The extraordinarily long lifespans listed here may reflect later editorial efforts to reconcile inconsistencies in the imperial chronology.

2. Why Is 660 BCE Considered the Beginning of Japan?

There is a long-standing belief that Japan was founded in 660 BCE. But how was this particular date determined?The clue lies in the introduction of the Chinese calendar system during the reign of Empress Suiko. This system is based on the combination of the Ten Heavenly Stems (甲, 乙, 丙, 丁, 戊, 己, 庚, 辛, 壬, 癸) and the Twelve Earthly Branches (子, 丑, 寅, 卯, 辰, 巳, 午, 未, 申, 酉, 戌, 亥), along with the Five Elements (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water). These cycle in a sexagenary (60-year) pattern.

Within this cycle, particular importance is placed on the year "Shin'yū" (辛酉), traditionally seen as a time of great transformation. When this "Shin'yū year" occurs for the 21st time (i.e., after 1,260 years), it is regarded as an especially significant turning point.

By calculating 1,260 years backward from Empress Suiko's era, the result was 660 BCE—a date then retrospectively established as the foundation year of Japan. From there, emperors were assigned along the timeline to fill the gap.

To make the chronology line up, emperors for whom no birth or death records existed were given implausibly long lifespans. This suggests that, while official records were lacking, these sovereigns—referred to at the time not as emperors (tennō) but as great kings (ōkimi)—were real figures whose existence could not be ignored.

If these rulers had been entirely fictional, one might expect the compilers to invent additional names or adjust the sequence more freely. The fact that they did not suggests these individuals were part of an established oral or local tradition and thus could not be arbitrarily added or removed.

This leads to a crucial question: If these nine kings did exist, is it possible to determine their actual historical dates?

3. Himiko and Historical Sources — From Myth to Record

In early Japan, written records did not yet exist. Himiko is mentioned solely in Chinese historical texts, most notably the Records of Wei on the People of Wa (魏志倭人伝, Gishi Wajinden), a section of the Records of the Three Kingdoms (三国志).Before the Wei dynasty, China was ruled by the Later Han. Its official history, the Book of the Later Han (後漢書), includes a chapter titled "Eastern Barbarians" (東夷伝), which records that the countries of Wa (Japan) and Nakoku sent envoys to China.

In 57 CE, the King of Nakoku is said to have paid tribute to the Han court and received a golden seal inscribed with "King of the Na state, vassal of Han" (漢委奴国王). This event is famously depicted in Japanese history textbooks.

Later, in 107 CE, a ruler of Wa is recorded to have offered 160 slaves to the Han court. Then, in the late 2nd century, widespread internal unrest in the Wa region—referred to as the Great Disturbance of Wa—is documented. It is within this context that Himiko emerges in the Chinese accounts.

Taken together, these accounts imply that by the first century CE, centralized leadership—perhaps in the form of a great king—had already begun to take shape. While speculative, it is not unreasonable to situate the era of Emperor Jimmu around this same period.

By the time of the Wa unrest in the late 2nd century, the stage had been set for Himiko's appearance. Though the term "Yamato court" may be anachronistic, if we adopt it for convenience, we can begin to position Himiko within the broader flow of its early development.

◆ Coming Next: The Origins of Himiko

In this installment, we explored the background of Japan's traditional founding and the historical context in which Himiko emerged.

In the next bottle, we will examine the origins of Himiko herself.